Bill Stone, Contributor

Bill Stone, Contributor

Nov. 21, 2022

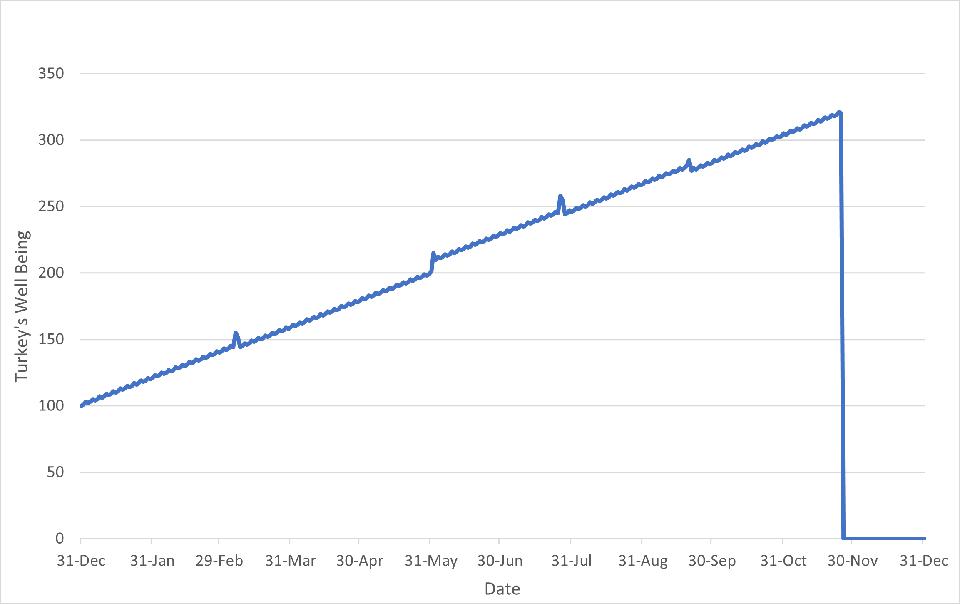

Thanksgiving seems an appropriate time to consider the “Turkey problem” as it relates to risk management. Nassim Taleb introduced the world to the “Black Swan” concept and used this example to illustrate the issue.

Imagine the life of a turkey where a kind farmer feeds and tends to it every day until suddenly, on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, the situation takes an irrevocable turn for the worse. The turkey has only observed a positive trend during its lifetime up until that fateful Wednesday and is the fattest and happiest at a point that turns out to be the time of maximum risk. It recalls another favorite quote attributed to Mark Twain: “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

A Year In The Life Of A Thanksgiving Turkey/Glenview Trust, Nassim Taleb

Interestingly, expecting trends to continue is an automatic human response to our built-in tendency for our brains to see patterns even when they do not exist. According to Jason Zweig in Your Money & Your Brain , this propensity to look for patterns makes sense since our primitive brains were tuned to the immutable physical laws of nature, like when lightning strikes, thunder follows. Stocks and the financial markets do not follow the rules of nature, so our trend-seeking behavior can often lead us astray. In addition, humans also suffer from “recency bias.” In other words, we weigh the more recent experiences more heavily when predicting future outcomes. This bias is why people expect stocks to continue to rise if they have increased recently. To be fair, there is evidence of autocorrelation and momentum in stock returns, but this is not an unfailing natural law. Instead, this tendency for stocks performing well to continue to perform well does not work all the time, and the signal tends to reverse eventually. Investors using momentum need to have a disciplined process implemented across a portfolio of stocks with a strict sell discipline.

Probably the best way to combat the pernicious influence of the unconscious primitive mind when making investment decisions is by using historical data to make informed projections about the likely returns and risks. For example, could anyone have reasonably predicted that bonds might not always serve as a safe harbor when stocks decline? The S&P 500’s total return was down almost 25% from its January peak at its worst in October, while bonds provided no actual shelter from the storm. This year the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond index was down almost 17% from its peak, and the Bloomberg U.S. Treasury Long index was punished at -35%.

First, looking at history, the bond market has had more significant declines at times than most would imagine since many people investing now have seen little evidence of high inflation or yields in their lifetime until recently. According to Sidney Homer and Richard Sylla in A History Of Interest Rates , the greatest of all bond bear markets in the U.S. was from April 1946 to September 1981. The yield on long-term U.S. government bonds rose from 2.08% to 14.14%. If an investor had owned a constant maturity 30-year bond during this period, the value would have declined by a whopping 83%! While this decline overstates the damage done to typical bond investors since most don’t constantly own the interest rate risk of 30-year bonds, the idea that bonds don’t carry risk is spurious.

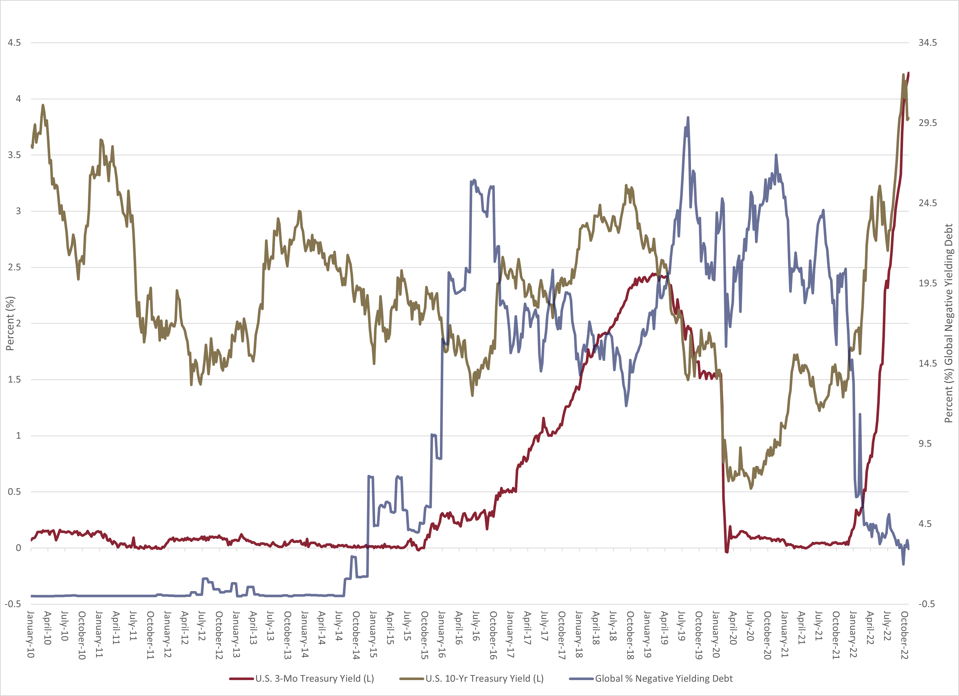

Second, mathematically the best estimate of the future returns from a bond is the yield of that bond. For example, if one buys a 10-year U.S. Treasury yielding 3.8% and holds it to maturity, the annualized return will be 3.8%. Thus lower yields imply lower forward returns. However, this expectation doesn’t work all the time since bond yields can always go lower, and we have even seen negative yields. When yields fall, and an investor owns a bond with a higher promised yield, the total return is higher than the stated yield. If all this discussion of bond math doesn’t interest you, the bottom is that lower yields make bonds riskier, not safer, even though these lower yields are happening after a strong performance from bonds.

In more recent history, the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield fell to about 0.5% during Covid, and short-term yields dipped into negative for a bit. Amazingly, nearly 30% of the bonds in the world had negative interest rates during the Covid panic. These facts aren’t to say that everyone should have sold all their bonds, as there was clearly a possibility that the world could have sunk into a severe recession and deflation that would continue to benefit bonds. It’s just a realization that forward returns were likely to be poor from those levels, and risks had risen. So consideration should be given to lowering the interest rate risk in portfolios, holding more stocks than usual, or having some alternative investment exposure to diversify risks.

Bond Yields/Glenview Trust, Bloomberg

Bonds might not be the best analogy to illustrate the turkey problem since they mature at face value, assuming no credit problem, even if purchasing power may have been lost. Investors must beware when the trends look obvious and making money seems effortless: “the same hand that feeds you can be the one that wrings your neck.”

© 2022 Forbes Media LLC. All Rights Reserved

This article was reprinted with permission by Forbes Media. The views expressed herein are those of Bill Stone, Forbes contributor, and do not necessarily reflect the views of The H Group.

This Forbes article was legally licensed through AdvisorStream.